While you are rather accustomed to having nice photos with my blog posts, this time you are going to get lots of words–maths words. With lots of problems!

Formula: Math x English = Problems.

In British (and Kiwi and Australian) English, math becomes maths. But that is only the beginning of the problems with math in English; or in terms of teaching math in the Church Schools, English is a big problem! (Since some of you in the family have taught math, I hope these examples make you laugh.) Take these recent discoveries as examples.

While we were doing training in Samoa, we talked about the problem of teaching math in English with some primary school teachers. In primary school, the students do not really know very many words in English. However, some easy, simple words in English have math meanings–is, and, more than, less than, in [a set], makes, times. The students might know “What time is it?” but not know that times is a synonym for multiply.

In the training, the teachers added more words to our list. I could tell they understood the problem a little. Later in the afternoon after our training, however, Jonathan (from the Schools Team) asked some teachers what at least meant. Four teachers were in the room when he asked. They didn’t know, even with an example given as a math word problem. If the teachers don’t know, the students cannot know either.

Native speakers of English might think that phrases like at least are very easy to understand. The teachers all thought it meant the opposite of its meaning: equal to or less than rather than equal to or greater than.

Other examples of English word problems for math might be take away (for subtraction) or count up (for addition). Research shows that the 10-12 most common verbs + prepositions can equal at least 40,000 meanings!

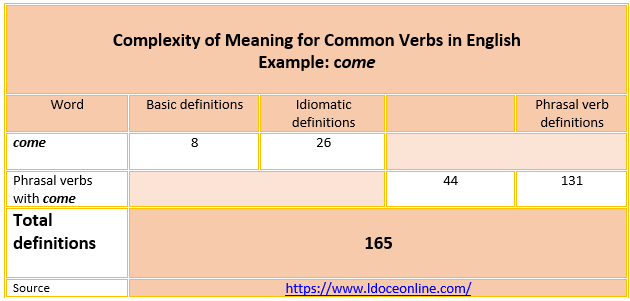

Look at this example of the word come. Using a dictionary for English language learners, here is an analysis of the complexity of using the “easy” word come. (From Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Online: https://www.ldoceonline.com/). Idiomatic definitions include meanings for phrases such as: have come a long way, come clean, come as a surprise, etc. Phrasal verbs are verbs plus a preposition (or two), such as come up or come over.

As you can see, a simple word like come, which is usually learned very early, can be more difficult than you might think. Within the 165 possible meanings for the word come, some definitions give math meanings (or senses) for that word. For example, come can mean “order,” as in “She came in third in the 200 meter race.” This meaning could easily be used in a math word problem. Here is another example: come to, with the meaning of “add up to,” as in “The total bill came to $54.31.”

How do math teachers come to know [a rather difficult use of the word come] these are “math” words and need to be taught by them and not English teachers? And because there are many simple words like come that can have a math meaning, the problem could be overwhelming for teachers. Can you, for example, think of a math usage for any of these words?

find get give go let make take

(don’t forget adding prepositions might make them math words, too, such as take away or go into)

That is the problem I’m working on now. (Which, at times, is driving me crazy.)

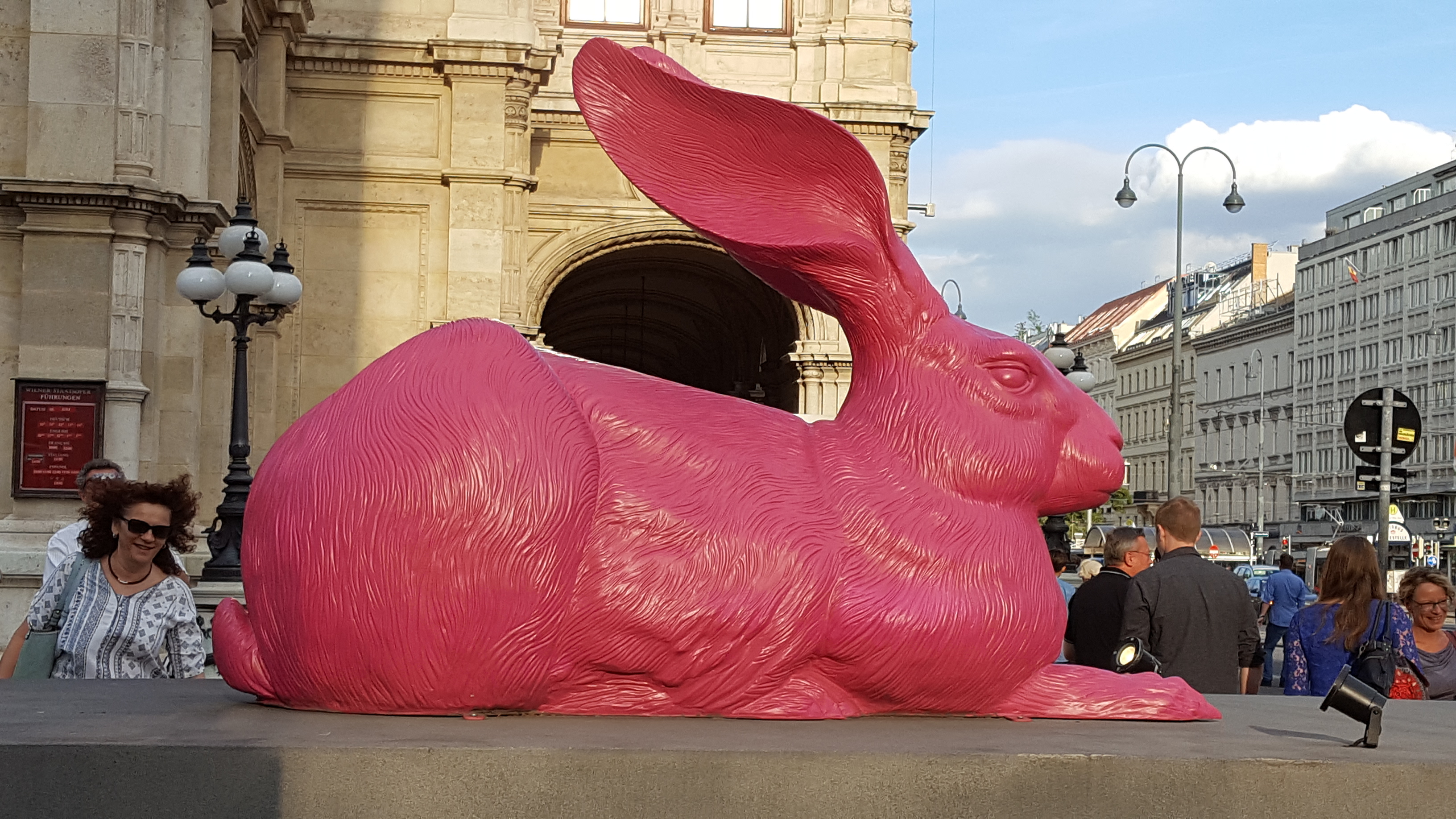

I have added the photo to the left just to give some color to my post, but perhaps I could turn it into a math problem. Count the plants? Subtract the plants with flowers from the plants without flowers? Determine the number of coconut husk parts required to make a full coconut husk. Crazy.

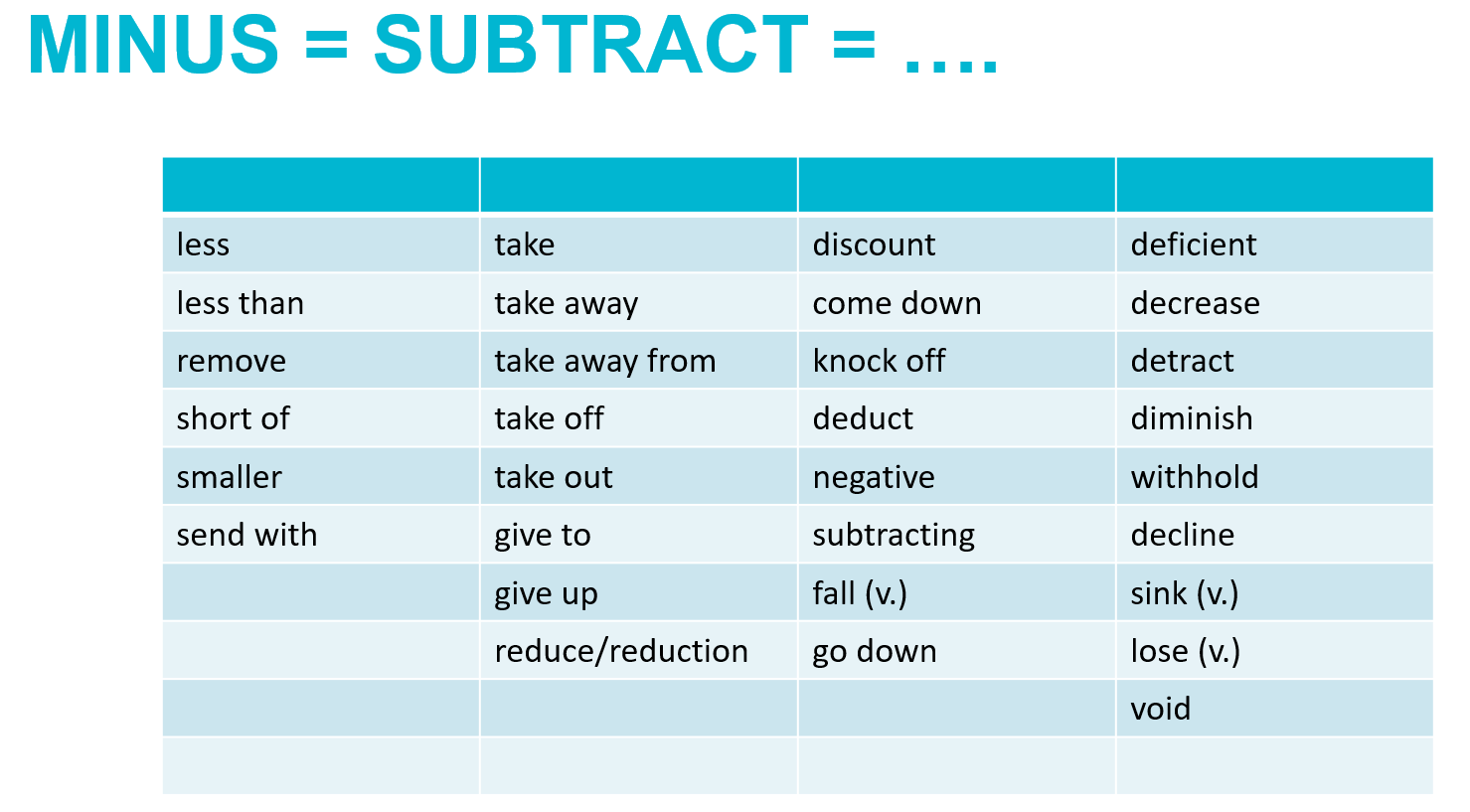

Another problem I’m working on is the problem of synonyms for words that are clear math terms. Here is a problem we encountered. One of the members of the Schools Team was giving a diagnostic math test at a middle school in Tonga. While giving the test, the school principal (a former math teacher) was wandering the classroom, watching the students take the test. One question on the test asked the students what “something minus something” was. Most of the students were missing the question. The proctor heard the principal tell the students that minus meant subtract. After receiving that information, all the students got that question correct when the tests were graded. Since it was a diagnostic test and the proctor heard what happened, it didn’t really interfere with our diagnosis of what might be important difficulties in teaching math in English. The key takeaway: The students do not know common synonyms for essential math terms.

Hearing that story sent me on a quest for finding useful synonyms for common math terms. Here is my list (right now) for synonyms for minus/subtract. I keep finding more to add (and then I have a list of words that mean add, multiply, divide….)

Here is an example of a math problem I found in a textbook for New Zealand students. Can you see what might make this difficult for students that are still learning English?

The first English problem that most teachers would see is the unusual word wētā ? Look wētās up on the Internet because you will be amazed at them. I have only heard these insects singing at night but have never seen one myself and, therefore, don’t have a photo. Wētās are some of the largest insects in the world and are endemic to New Zealand. They seem mighty big to me. (I hope to see one before I depart, but I’m not sure I would like one to hop on me.)

https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/invertebrates/weta/

Back to the math problem… wētā is not really the most difficult problem. It is a word where the math can still be done without knowing the meaning. I see a list of other English words that are more likely to cause difficulties with Year 7 students (who may have studied English for only a few months). Words they might not know yet include pie used as other than food, graph, in the wild, quarter, and diet. A little harder are two-part words like most of, least of, other than, and part of, or the three-part phrase made up of.

But really! Can anyone tell me why the last question, “Why are the birds such a small part of the rat’s diet?” is a math question? It sounds more like a science question to me.

To close out this crazy maths post, let’s have another photo of the lovely gannet birds (who are not “at home” in New Zealand right now). Do you know why rats in the wild don’t eat these birds? (Neither do I, although gannets are quite large birds, which might keep them safe even if they do nest on the ground.)

Corinth has been inhabited for more than 5,000 years. Much of the ancient Greek city was destroyed and rebuilt by the Romans, the city where Paul would have lived (about 51-52 AD). Paul stayed in Corinth nearly 2 years.

Corinth has been inhabited for more than 5,000 years. Much of the ancient Greek city was destroyed and rebuilt by the Romans, the city where Paul would have lived (about 51-52 AD). Paul stayed in Corinth nearly 2 years.

Corinth is an ancient, thought-producing place to visit.

Corinth is an ancient, thought-producing place to visit.

Part of the striking nature of the town is the mountains that surround it in the back, which you can see behind the church towers, along with the water in the front. The mountains were used for defense, with fortifications built along the ridge. There are over a thousand steps if you want to climb to the top.The town also had moats and walls at sea level.

Part of the striking nature of the town is the mountains that surround it in the back, which you can see behind the church towers, along with the water in the front. The mountains were used for defense, with fortifications built along the ridge. There are over a thousand steps if you want to climb to the top.The town also had moats and walls at sea level.

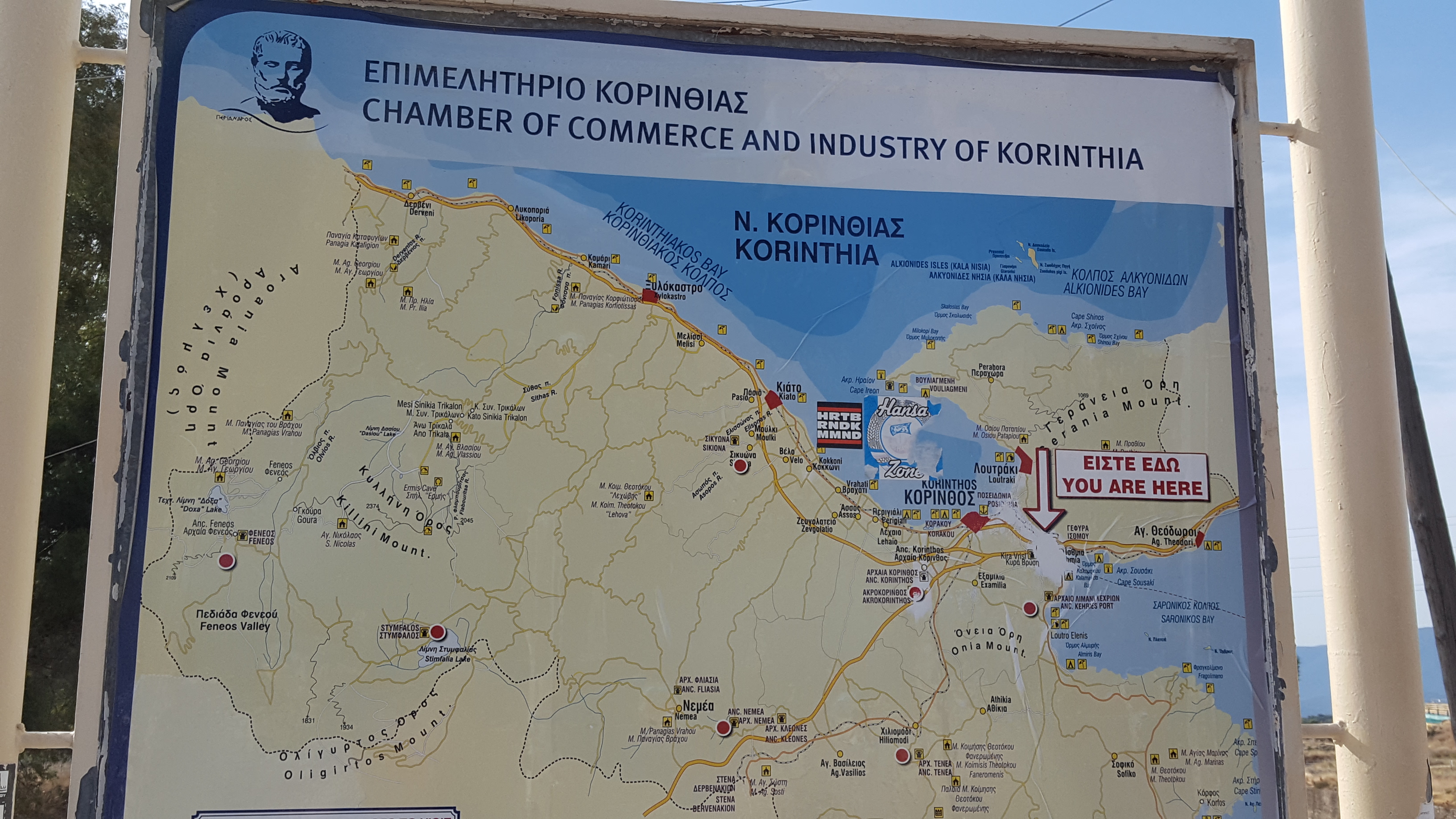

When I saw on the map the complex shape of the bay, I determined I was going to the top deck of the cruise ship to watch our departure (since I had missed the arrival during the night).

When I saw on the map the complex shape of the bay, I determined I was going to the top deck of the cruise ship to watch our departure (since I had missed the arrival during the night).